Big Cats Suffer in Traveling Acts

In March 2020, the world got a glimpse of the dark underbelly of roadside zoos across America in Netflix’s Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness. The docuseries detailed events leading to big-cat breeder and abuser Joseph “Joe Exotic” Maldonado-Passage’s convictions for 17 counts of wildlife-related federal crimes, including killing five endangered tigers and trafficking in endangered animals, and for hiring someone to murder the owner of an accredited sanctuary that rescues big cats from roadside zoos and the entertainment industry.

Tiger King exposed millions of viewers to the worst practices of cub-petting operations, which continually churn out big-cat cubs, tear them away from their mothers, and sell high-dollar public interactions with them. Those who survive the short window of time in which they’re small enough to be handled may be illegally sold, given away, or killed. But the cub-petting industry has suffered a series of devastating blows, particularly as a result of PETA’s legal challenges, and thankfully, with heightened public scrutiny, its days are numbered.

But cruelty to big cats extends far beyond the roadside zoos and shady individuals featured in Tiger King. Each year, often for months at a time, traveling exhibitors cart lions, tigers, and other big cats to circuses, fairs, and other roadside attractions across the country. Over a dozen of these exhibitors operate in the United States, collectively imprisoning more than 80 of these animals and depriving them of everything that is natural and important to them.

From the Serengeti plains to the birch forests of Russia, lions and tigers in nature control vast home territories defined by complex social systems and familial bonds. Lion and tiger cubs stay at their mothers’ sides for years—and female lions remain with the pride into adulthood. Adept hunters, big cats may travel many miles in search of prey, a gratifying pursuit that is essential to their survival and psychological well-being. Traveling displays deny big cats any opportunity to engage in the behaviors that define them.

Through violence and intimidation, trainers break the spirits of the big cats they force to perform, stripping them of their essence and leaving them a shell of their natural selves. The allure of these displays—the control and taming of wild animals—relies on this abuse and promotes and reinforces dangerous beliefs about human supremacy and dominance over nature and animals. The continued exploitation of big cats in traveling displays threatens not only the individual animals forced to perform demeaning, confusing tricks under the threat of violent punishment but also the entire species they represent to audiences that fail to see them for who they are.

Traveling Exhibits Fueled by Joe Exotic and the Cub-Petting Industry

One question rarely asked of traveling exhibitors is how an animal winds up in a cramped trailer, headed down the interstate to a performance in the first place. The answer is closely guarded by the industry, and poor regulatory oversight makes it difficult to verify where traveling exhibitors obtain big cats and other animals. But the fingerprints of Maldonado-Passage and other Tiger King figures can be found all over circuses and other traveling animal acts.

Disgraced exhibitor Doug Terranova has supplied tigers and other animals to the Carden International Circus, Shrine circuses, and the Culpepper & Merriweather Circus, as well as fairs across the country. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates animal exhibitors, revoked his exhibitor’s license for “willful, repeated, and prolonged violations” of the Animal Welfare Act. He also has close ties to Maldonado-Passage: Terranova served as Maldonado-Passage’s running mate during the latter’s failed 2016 presidential campaign and claims to have obtained a dozen big cats from Maldonado-Passage and fellow Tiger King subject Bhagavan “Doc” Antle over the years. He is also involved with the misleadingly named National Animal Welfare Association, which promotes traveling tiger acts and lobbies against animal protection legislation.

Before the 2008 circus season, Culpepper & Merriweather Circus owner Trey Key boarded sibling tigers Solomon and Delilah—both of whom are still being forced to perform with the circus today—as well as a lion named Francis at Terranova’s facility in Kaufman, Texas. Terranova apparently failed to separate the cats, and in May 2008, while on tour, Delilah gave birth to three cubs presumably fathered by her brother. Within days, two of the inbred cubs died. In August, the lone survivor, named Tubbs, was confiscated by the USDA after he was found in the cab of Terranova’s truck at the Iowa State Fair. The temperature in the truck—which had no air conditioning—was over 89 degrees Fahrenheit. Tubbs was underweight and had skin abrasions from an ill-fitting harness and a wound near his eye. A USDA administrative law judge found that Key “demonstrated a shockingly cavalier attitude regarding the health and safety of animals” and suspended the circus’s license.

While this instance of inbreeding could have been accidental, the cub-petting industry is notorious for unscrupulous breeding practices. Breeders often selectively breed big cats for specific physical traits, such as the recessive white or golden color morphs, which can have disastrous consequences for an animal’s health and well-being.

The initial population of white tigers in the U.S. could be traced to a single individual who was bred to his own daughter, while the current U.S. population stems from crossbreeding two tiger subspecies. To preserve the recessive trait that is responsible for their white coats, white tigers—who are commonly used in traveling acts—are highly inbred, which can lead to increased susceptibility to disease, premature death, stillbirth, and debilitating deformities, such as cleft palates. Big-cat hybrids are also at high risk for genetic defects. Ligers (the result of breeding a female tiger with a male lion—two entirely different species who do not cross paths in nature) can grow so large that their organs cannot sustain their own weight. Roadside zoos and backyard breeders such as those featured in Tiger King breed suffering into big cats, and that suffering is exacerbated by a life of exploitation, often at the hands of traveling exhibitors.

Maldonado-Passage told PETA that Ryan Easley (aka Ryan Holder)—who owns ShowMe Tigers; is planning to open a roadside zoo in Hugo, Oklahoma, called Growler Pines Tiger Preserve; and exhibits tigers at the Circus World Museum, Shrine circuses, and the Carden circus, among others—bought at least a dozen tigers from his Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park (G.W. Zoo) and boarded tigers there when they weren’t traveling for the circus. In 2019, Easley obtained two 8-month-old tigers—Jade and Amara—from Antle while performing at Circus World. These tigers were exploited on Antle’s watch from early on, and once they were too old to be used as photo props, he sentenced them to a life of demeaning circus performances under the threat of the whip.

In 2012, the now-defunct Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus purchased eight tigers from Maldonado-Passage. Before arriving at Ringling, they were held by the Carden International Circus. For Ringling exhibitors like big cat trainer Alexander Lacey, who toured with the circus until its final show in 2017, animal exploitation is a family affair. His mother, Susan Lacey, trained and presented tigers for the Hawthorn Corporation, a notorious breeder, dealer, and exhibitor. Dozens of tigers—including many juveniles—died on Hawthorn’s watch before it went out of business in 2017.

One of Ringling’s former elephant trainers, Terry Frisco, and his family run a traveling big-cat show called Tiger Encounter that appears at fairs with tigers exhibited by his daughter, Felicia Frisco. Felicia also exploits big cats to boost her social media following, frequently featuring a white tiger and a white lion in TikTok videos. According to research by Big Cat Rescue, the lion, named Shaka, appears to have been bred by Tiger King subject and former drug kingpin Mario Tabraue of the Zoological Wildlife Foundation. Like other big cats born at Tabraue’s facility, Shaka was likely torn away from her mother early on and used for cub-petting interactions. She was then apparently used in a film production and passed among various Florida-based exhibitors before landing in the Friscos’ custody around February 2019—just months after her birth, when she should still have been by her mother’s side. But the Friscos’ ties to the cub-petting industry don’t end with Shaka—Felicia Frisco also considered Maldonado-Passage and Antle close friends. Both of them have defended her from public scrutiny of her exploitation of big cats.

Maldonado-Passage also had his own traveling show, which he kept supplied with tiny cubs by constantly breeding big cats at his roadside zoo in Oklahoma. Cubs were torn away from their mothers immediately after birth and soon afterward taken to malls and fairs across the United States to be used as lucrative photo props. In 2015, Maldonado-Passage was cited by the USDA for failing to provide a 19-day-old tiger cub—who was too young even to regulate his own body temperature—with a secondary heating or cooling method for climate control while being exhibited at the Mississippi Valley Fair in Iowa.[xvi]

Ultimately, Maldonado-Passage’s ties to circuses and traveling acts helped secure the roadside zoo operator’s downfall. In October 2017, Key (of the Culpepper & Merriweather Circus) paid Maldonado-Passage $5,000 to house Francis, Solomon, and Delilah at G.W. Zoo. A worker at the facility testified that Maldonado-Passage used a shotgun to kill five healthy tigers in order to make room for Key’s big cats. Maldonado-Passage is currently serving a 22-year sentence in federal prison for these and other crimes, including trafficking in endangered animals and two counts of murder-for-hire.

Compliance Coerced Through Abuse and Punishment

Tigers, lions, and other big cats don’t leap through hoops of fire, balance on their hind legs, or perform other dangerous stunts because they want to—they engage in these unnatural behaviors under the threat of violence and physical punishment. USDA regulations prohibit training with physical abuse, but the agency does not actually monitor training, which occurs behind closed doors and out of the public eye.

In one of the most barbaric incidents caught on film by a PETA eyewitness, disgraced former big-cat trainer Michael Hackenberger—who supplied animals for circuses in Canada—whipped a tiger named Uno approximately 20 times in a row, causing him such trauma that he emptied his anal sacs in fear. Hackenberger matter-of-factly stated that he “like[s] hitting [Uno] in the face” and uses his whip to carve his initials into the animals’ sides.

In a 2017 investigation by the Humane Society of the United States, Ryan Easley (of ShowMe Tigers) was documented violently whipping tigers during training sessions. He reportedly whipped one animal over 30 times in less than two minutes.

While the worst violence occurs in secret, the pain, force, and fear used to dominate big cats plays out on stage and is readily observable to anyone willing to look beyond the loud music and bright lights. When performing in front of an audience, exhibitors keep their weapons close at hand, using them on the animals or cracking them on the floor, a constant reminder of the painful consequences of breaking routine. But no amount of training or physical abuse can overcome the instincts of tigers or lions, who will try to defend themselves as best they can—using their teeth and claws. In such instances, trainers’ reactions are swift and merciless.

At a 2017 Shrine circus performance in Florida, which featured a tiger act supplied by the now-defunct Hawthorn Corporation, an eyewitness documented handlers jabbing a tiger with poles from outside the ring after the animal apparently broke formation during a performance, causing the tiger to growl and spin in agitation. In 2016, stunned fairgoers observed trainers whip a tiger named Gandhi in the face 33 times after handler Vicenta Pages used her knee to push him toward a hurdle and he pulled her to the ground. Pages was filmed again prodding and whipping lions and tigers at the Tangier Shrine Circus in 2020, as the cats frantically tried to escape.

During the 2017 Martin County Fair in Florida, a tiger bolted in fear after trainer Juergen Nerger—who, with his wife, Judit, operates Nerger’s Lion and Tiger Show and carts animals to fairs and circuses across the country—repeatedly “jab[bed] him in the throat with a stick” and “[hit] him in the face,” according to a witness. Brian Franzen, who exhibits big cats at the Loomis Bros. Circus and Shrine circuses, has said he sprays cayenne pepper in tigers’ eyes and noses when they refuse to obey his commands.

Fearing such violence, big cats are often reluctant to enter the performance ring, so in an attempt to force them on stage, workers may jab them aggressively with prods. Once in the ring, their body language conveys fear and defensiveness.

While performing, big cats often hunch their backs, lower their heads, and pin their ears back, all signs of fear or submission. In the Tangier Shrine Circus video mentioned above, the cats growl—a defensive reaction—several times before finally bolting. Displaced aggression toward other cats, also apparent in the Tangier Shrine video, is common and exacerbated by extreme crowding and a lack of escape routes while in transport cages and on stage. Big cats’ anxiety about performing is further illustrated by the fact that their rate of stereotypic pacing behavior—which is associated with frustration, stress, agitation, and lack of mental stimulation, depending on the situation—peaks in the hour preceding a show.

Not only do abusive training methods cause psychological and physical harm, the tricks themselves can also be painful, uncomfortable, and frightening for the cats. Typical stunts performed in circuses and other shows involve unnatural postures and movements that are rarely seen in the wild because of the strain they place on the body. Performing animals forced to stand on their hind legs for long periods, for example, become susceptible to arthritis. Leaping through flaming hoops, another standard trick in circuses, is terrifying and dangerous for big cats, who are naturally afraid of fire. During a Russian circus performance, a tiger fell unconscious, convulsed, and emptied her bowels after being forced to jump through several hoops of fire. Horrified spectators watched as trainers dragged her away by the tail.

Denied Any Semblance of a Natural Life

Intensive Confinement to Cramped Transport Cages

In their natural habitats, tigers and lions roam territories of up to 500 square miles. Their environment is spatially complex and dynamic, which exercises not only their muscles, but also their minds as they make choices and experience a sense of purpose while navigating through dense vegetation or across plains or while climbing trees in search of prey and other resources. Big cats used in traveling acts, in stark contrast, are kept in close confinement for most of their lives, spending up to 99% of the time they are on the road—which can be up to 11 months a year—in cramped transport cages. These cages, typically kept in a trailer during transport, can be as small as 24 square feet, a fraction of the size of a parking space. For adult big cats, who can be nearly 10 feet long and weigh more than 500 pounds, transport cages barely offer enough room for them to stand up and turn around, much less any significant freedom of movement.

Traveling big-cat exhibitors commonly receive citations for failing to meet minimum space requirements. In June 2021, the USDA cited Adam Burck, a big-cat exhibitor who supplies animals to the Jordan World Circus and others, because he was storing four tigers in travel cages like equipment for at least 15 months. The inspector found the animals confined to the cramped cages inside a stiflingly hot barn that was crawling with maggots and had a rancid odor. Burck even has a written policy stating that his cats must be in transport cages “at all times” except when performing.

The Nergers have been cited by the USDA for confining tigers to cages so small that they couldn’t stretch or even sit upright. Similarly, trainer Brunon Blaszak has received at least seven citations concerning space requirements, including ones for keeping a tiger in a cage in which he couldn’t stand up without hitting his head and keeping tigers in transport cages for days at a time. In less than four years, from 2006 to 2010, Julius Von Uhl, who exhibited big cats at circuses, fairs, and other events, was cited at least 18 times for failing to meet minimum space requirements. In one instance, a USDA inspector noted, “These enclosures are so small that the animals contained don’t even have enough room to exhibit stereotypical signs of lack of space, such as pacing.” As a result of his repeated defiance of regulations, in 2010, the USDA finally confiscated six tigers and four lions from him.

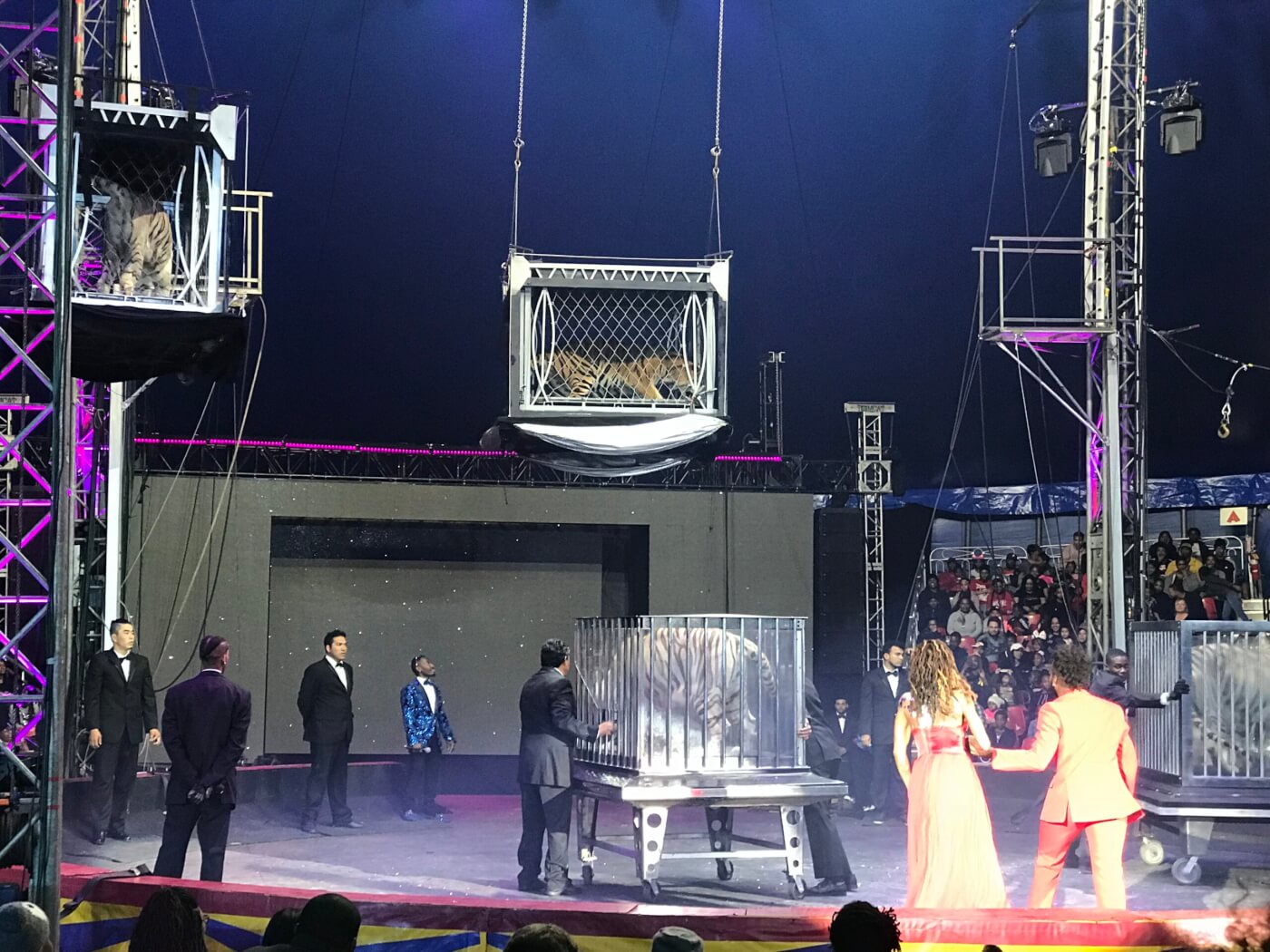

Some exhibitors justify the near-constant confinement to transport cages by claiming that training and performance sessions provide enough exercise and time outside the cages. But the truth is that big cats typically perform for just six to eight minutes per show, and their time in the ring can hardly be considered exercise. In a typical big-cat routine, the animals are forced to spend much of their time sitting still on pedestals and the rest performing unnatural tricks. And for some, being caged is the act: In a magic trick for the UniverSoul Circus, exhibitor Mitchel Kalmanson pressed tigers into hidden compartments of small cages, suspended them up in the air, and then made them “appear.” When not performing, they were kept in a converted semi-trailer. On two separate occasions in 2013, Kalmanson was cited for failing to offer the animals used in his act any opportunity to exercise or make normal postural adjustments.

Even when exercise pens are provided, they are usually small, barren enclosures in parking lots crowded with multiple cats or only provided on a rotational basis. In one study in which tigers used by Ringling Bros. were given unlimited access to an exercise pen for 72 hours, half of them exhibited pacing behaviors more than 10% of the time—one individual paced for 77.5% of the time—indicating “unacceptably compromised” welfare. Pacing is often seen in animals experiencing chronic stress, deprivation, or psychological distress. This demonstrates that the size and complexity of the pens are insufficient and that the long stints of confinement to transport cages are so damaging that they cannot be mitigated by merely providing cats with a slightly larger cage. A lack of adequate exercise and stimulation can cause obesity and behavior indicative of frustration, such as apathy.

Incompatible Social Groupings

Big cats used in traveling acts are housed in highly abnormal social groupings that contradict their territorial instincts. While tigers have long been considered solitary in a natural setting, recent evidence has shown that they may prefer social interaction with one other cat in captivity.

Living in groups larger than two individuals and having close neighboring tigers, however, has been shown to induce stress-related behavior, fighting, and pacing. Traveling acts do not have the space to provide separate accommodations for each tiger or pair away from other cats, forcing them to live in close proximity to each other with no means of escape or places to hide. To move tigers from the travel trailer to the performance ring, Brian Franzen uses an even smaller transport truck, cramming as many as half a dozen tigers into a cage that offers no place to retreat during conflicts.

Severe crowding and incompatibility can be deadly to big cats: A tiger owned by Vazquez Bros. Circus, which had previously been cited twice by the USDA for failing to meet minimum space requirements for tigers, was killed and nearly decapitated by her four cagemates in 2008 after being left overnight with them in a small cage. Even after this horrific incident, Vazquez Bros. was cited because it was still keeping five tigers in a cage half the size of a semi-trailer.

Inappropriate Feeding and Inadequate Nutrition

In nature, tigers spend most of their time looking for prey, traveling efficiently and purposefully, as if using a mental map of their territories. To a tiger, hunting is more than a means to find food—it is psychologically fulfilling, it reinforces a sense of accomplishment, and it promotes positive feelings, improving mood, perception, memory, and attention. It also improves their physical strength. In recognition of this crucial aspect of big-cat welfare, reputable captive wildlife facilities, such as those accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), maintain enrichment programs that encourage tigers and other big cats to engage in simulated hunting, stalking, and foraging behaviors.

In contrast, traveling exhibitors deny big cats any opportunity to engage in these important species-specific types of behavior, disregarding the very essence of their being.

As part of a properly formulated and complete diet, whole-carcass feeding can play an important role in promoting species-appropriate behavior in big cats in captivity. In one study conducted at three AZA facilities, carcass feeding decreased the number of abnormal repetitive behaviors observed off exhibit. These feeding methods are nearly impossible to implement while on the road, where a lack of consistent access to reliable food sources often leaves exhibitors no choice but to take whatever meat is available. For large carnivores, the psychological toll of an unnatural feeding regimen can be profound, and this inconsistency—combined with traveling exhibitors’ reliance on employees with no training in animal nutrition or husbandry—can have serious implications for a big cat’s physical well-being and increases the risk of illness and malnutrition. For example, a lion cub owned by Mitchel Kalmanson, whose list of animal-welfare violations includes inappropriate feeding, died of metabolic bone disease, caused by a calcium-deficient diet. A poor diet combined with a lack of exercise leaves big cats used in traveling acts at higher risk of joint and spine conditions, difficulties regulating their body temperature, and obesity, which can cause heart and organ problems.

A Dangerous, Demanding Life on the Road

Stress during transport is a well-known problem in animal welfare, and big cats face unique challenges on the road. During the performance season, animals may be traveling several times a week or even daily, exposed each time to stressful circumstances such as sleep disruption, disordered eating and drinking, human handling, temperature and motion changes, noise, and close confinement. Tigers in one study transported for as little as 30 minutes had a respiration rate that was at its highest 10 minutes after being released and stress hormone levels up to 480% above normal for up to 12 days after their ride, suggesting that transport stress continues long after the experience is over.

Loading and unloading from the transport cage and trailer—perhaps the most stressful aspect of traveling—can cause a tiger’s body temperature to rise. This is of particular concern, as felines are sensitive to temperature changes and have a limited ability to sweat, instead relying on panting, shade, and immersion in water to regulate their body temperature. Close confinement and extreme crowding, combined with poor ventilation in transport trailers, contribute to fatal incidents in which big cats have died of heatstroke while traveling.

In July 2004, a lion named Clyde—who was being transported across the Mojave Desert in a Ringling Bros. boxcar—died after reportedly not being checked on or given water in six hours as temperatures exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The manager reportedly refused to stop because they were running late. Ringling had been cited by the USDA in 2000 for a similarly tragic story, in which two tigers injured themselves trying to escape from a hot boxcar.

Temperature management is a factor at the performance site as well. A common traveling act setup in a parking lot offers little to no shade and no climate control. Having access to a pool has been found to be the most important factor associated with good tiger welfare, but a pool is almost never offered to big cats while on tour. Jordan World Circus was cited for keeping a tiger named Dutchess in a poorly ventilated trailer with no water in temperatures over 95 degrees Fahrenheit, after having been cited just one week earlier for failing to provide two big cats with shade in similar temperatures.

Big cats—whose hearing is about five times better than that of humans—are very sensitive to the unending noise that comes with transport and exhibition, whether being hauled around in a truck or languishing in a crowded parking lot with loud music blaring. Tigers are also sensitive to vibration and infrasound, such as that created by diesel engines, airplanes, and turbines. Constant exposure to noise can have an adverse impact on a big cat’s physical and psychological health. Tigers are susceptible to gastroenteritis when exposed to noise for prolonged periods, and there is even evidence that noise pollution can alter animals’ physiological and immune processes because of DNA damage and modified gene expression. Visitor density, proximity, and noise level can contribute to an increase in pacing, decreased social interaction, high levels of stress hormones, increased vigilance, and hiding behavior in big cats. But there is nowhere for them to hide and no way to shield themselves from the rigors of life on the road.

Paper Tiger Laws

Cruelty-to-animals laws, which exist at the state and municipal levels, generally criminalize neglect and the intentional infliction of harm on animals. But they fail to protect big cats in any meaningful way: They don’t ensure that cats are held under optimal or even acceptable conditions, and enforcement is rarely, if ever, pursued against traveling big-cat exhibitors. This is because prosecutions are slow and resource-intensive and require considerable expert assistance to assess the victims, i.e., exotic animals, with whom U.S. authorities are largely unfamiliar. Moreover, circuses and fairs have normalized the caging, whipping, and exploitation of lions and tigers as objects of entertainment, and law enforcement may altogether fail to recognize these conditions as abusive. Thus, because traveling animal exhibitors only remain in a locality briefly—from hours to days—they can easily evade legal repercussions for their neglect and abuse of animals.

Some regulating agencies allow traveling exhibitors to skirt minimum caging requirements as long as the animals are only “temporarily” in the state or on the road for a certain number of days in a specified period. For example, many traveling exhibitors permanently reside in Florida but travel with the animals so frequently that the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission deems them “mobile exhibits” and allows them to keep animals in the state without having larger permanent enclosures. In other words, animals used by these exhibitors have no spacious “home” to which they return and rest—some may languish for years in cramped, barren transport cages, only occasionally released for exercise. In this case, the law doesn’t just look past abusive conditions—it permits them.

State and local officials often defer to the USDA, which licenses exhibitors under the Animal Welfare Act (AWA). Federal regulations implementing the law are minimal and vague; there are no standards tailored specifically to big cats or designed to ensure that exhibitors are providing them with optimal conditions and expert care. As a result, exhibitors may subject animals to extraordinarily inhumane conditions and still receive a “clean” USDA inspection report. For example, the law does not require exhibitors to allow mothers to raise their cubs until natural weaning or to provide tigers with basic necessities such as a pool for enrichment and thermoregulation. Nor does it expressly prohibit prolonged confinement, housing big cats on concrete, or other abusive practices that cause them physical and psychological suffering.

Additionally, in recent years, the USDA’s enforcement of the AWA has reached an unprecedented low. As documented in multiple Washington Post exposés, the number of AWA citations issued by the USDA dropped by 65% between 2016 and 2018, and the number of enforcement actions—which can result in fines and license revocation—dropped by 92%. Federal officials have reportedly even prevented the seizure of suffering animals. The USDA has prioritized protecting and cooperating with licensees (whom it now calls “customers”) over taking meaningful enforcement action.

Tigers and lions are also protected by the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), which makes it illegal to “take” protected animals (meaning “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.”). However, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), which is charged with enforcing the law, rarely enforces this “take” prohibition to challenge the conditions under which captive animals are held. The law does authorize citizen suits, which PETA has used to establish precedent that subjecting protected big cats to inadequate conditions of confinement, denying them adequate veterinary care, forcing them to interact with the public, and separating cubs from their mothers without medical necessity all violate the ESA. But citizen suits are no substitute for consistent enforcement by the FWS.

The ESA also prohibits commercial exploitation of protected animals. For example, it is illegal to transport endangered animals “in interstate … commerce in the course of commercial activity” without a permit. However, the FWS interprets “commercial activity” to extend only to sales (“the actual or intended transfer” of animals “from one person to another in the pursuit of gain or profit”), so it allows traveling exhibitors, who transport protected big cats across the country and use them to sell tickets at circuses and magic shows to escape regulation as a “commercial activity” under the ESA.

Improved federal standards and oversight of big-cat exhibitors is sorely needed, but life on the road is fundamentally inconsistent with the well-being of lions and tigers, who need space, a complex natural environment, and peaceful surroundings in order to thrive. This is why performance venues and legislators are increasingly opting to ban traveling animal acts altogether.

Deceptive Conservation Claims

Following the script of the roadside zoos and the backyard breeders from which they obtain big cats, traveling exhibitors often falsely state that their entertainment acts and their breeding of tigers, lions, or other endangered species—who are denied all semblance of a natural life and will never be released from captivity—help ensure the survival of a species and prevent extinction. They often even claim that “there is no wild” and that big cats are safer in circuses than in nature. These flimsy defenses of animal exploitation are nothing more than an effort to keep their businesses afloat by lulling unwitting families into buying tickets and by making audiences feel better about paying to see a caged tiger forced, under threat of the whip, to perform tricks in a circus ring.

In reality, seeing an animal in a circus or performing tricks does nothing for their counterparts who roam free in nature. Research confirms that such displays actually harm true conservation efforts. In a 2011 study published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, zoogoers were asked whether they thought chimpanzees were endangered. Most respondents erroneously believed that they weren’t because they saw them so frequently in the entertainment industry. For this reason, zoo-accrediting bodies have adopted policies opposing the use of apes in entertainment. Applying the same concept to tigers—whose numbers in their natural habitats in the U.S. are, according to some estimates, a fraction of the captive population—reveals a similarly troubling message. Big-cat displays can lead children and others to believe that the species they’ve watched performing in a circus ring don’t face extinction, as well as teaching audiences the dangerous lesson that it’s acceptable to interfere with wild animals for profit and “entertainment.”

Hope for the Future

But there is hope for big cats used in traveling acts. With rising public awareness of animal-welfare issues, audiences have largely turned away from the use of animals in entertainment, and in recent years, many traveling exhibitors—most notably Ringling Bros.—have succumbed to public pressure and gotten out of the business of exploiting animals altogether. Nearly 750 venues and dozens of communities across the U.S. prohibit or restrict traveling acts that use animals, making it increasingly difficult for exhibitors to map a profitable tour.

No tiger, lion, or other wild animal belongs in a circus ring, at a county fair, or at any roadside display. To patrons, such exhibits are a temporary attraction, only in town for a short time before packing up and fading from memory until the following year. For the animals forced to perform in them, travel and exploitation is a permanent condition. The cycle of abuse never ends.

A life of transport and performance denies big cats everything that is essential to who they are. The unceasing demands of travel and exhibition, combined with the completely unnatural and inadequate conditions they’re forced to endure, result in a lifetime of psychological and physical trauma.

With little oversight and rare repercussions for documented violations of federal regulations, exhibitors abuse, deprive, and neglect big cats with relative impunity. Fueled by roadside zoos and backyard breeders, traveling big-cat exhibitors endanger and harm the very animals they claim to be conserving, but by refusing to buy a ticket to these displays, consumers can usher in a more compassionate future and help end the exploitation of big cats used in entertainment.